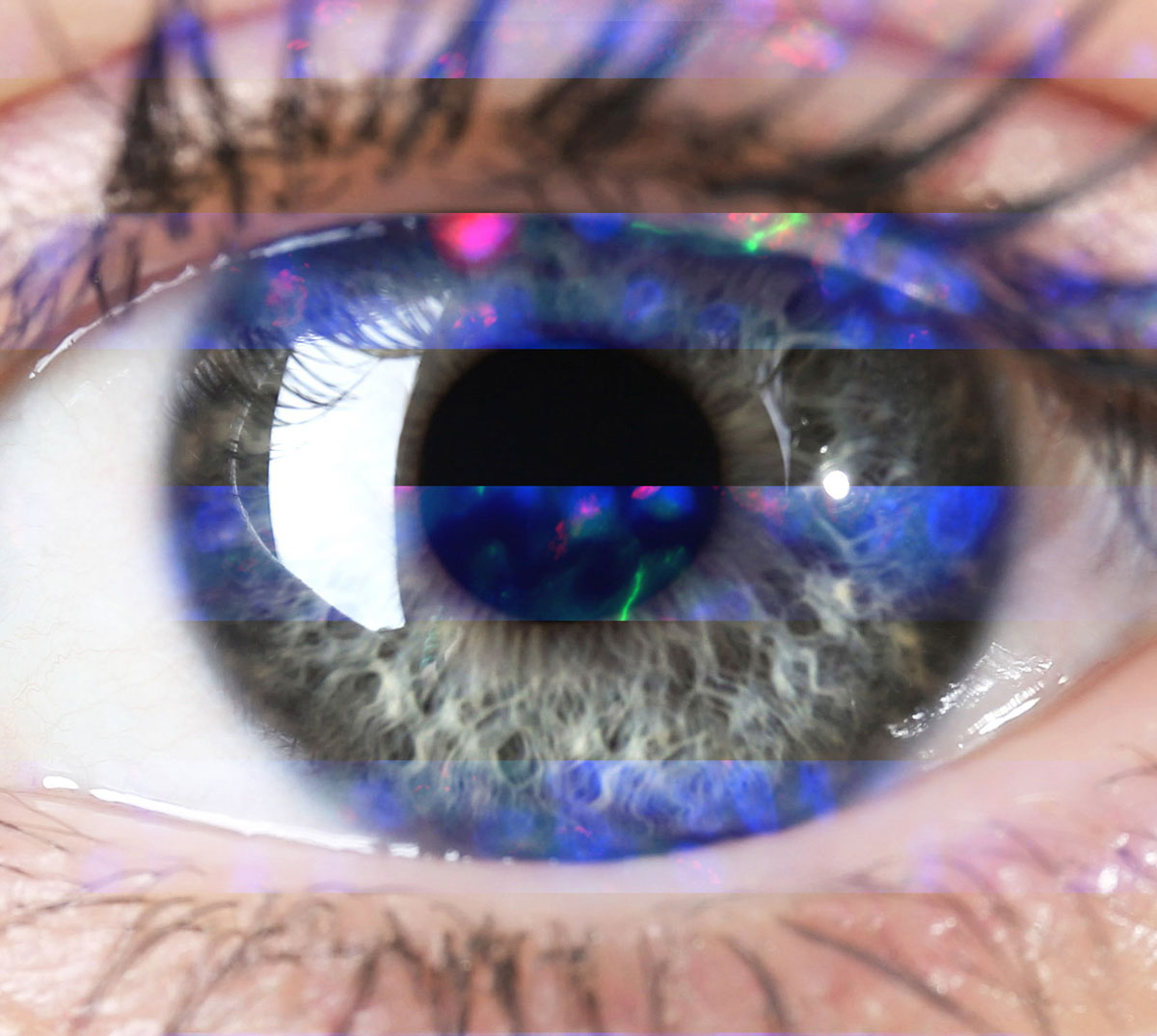

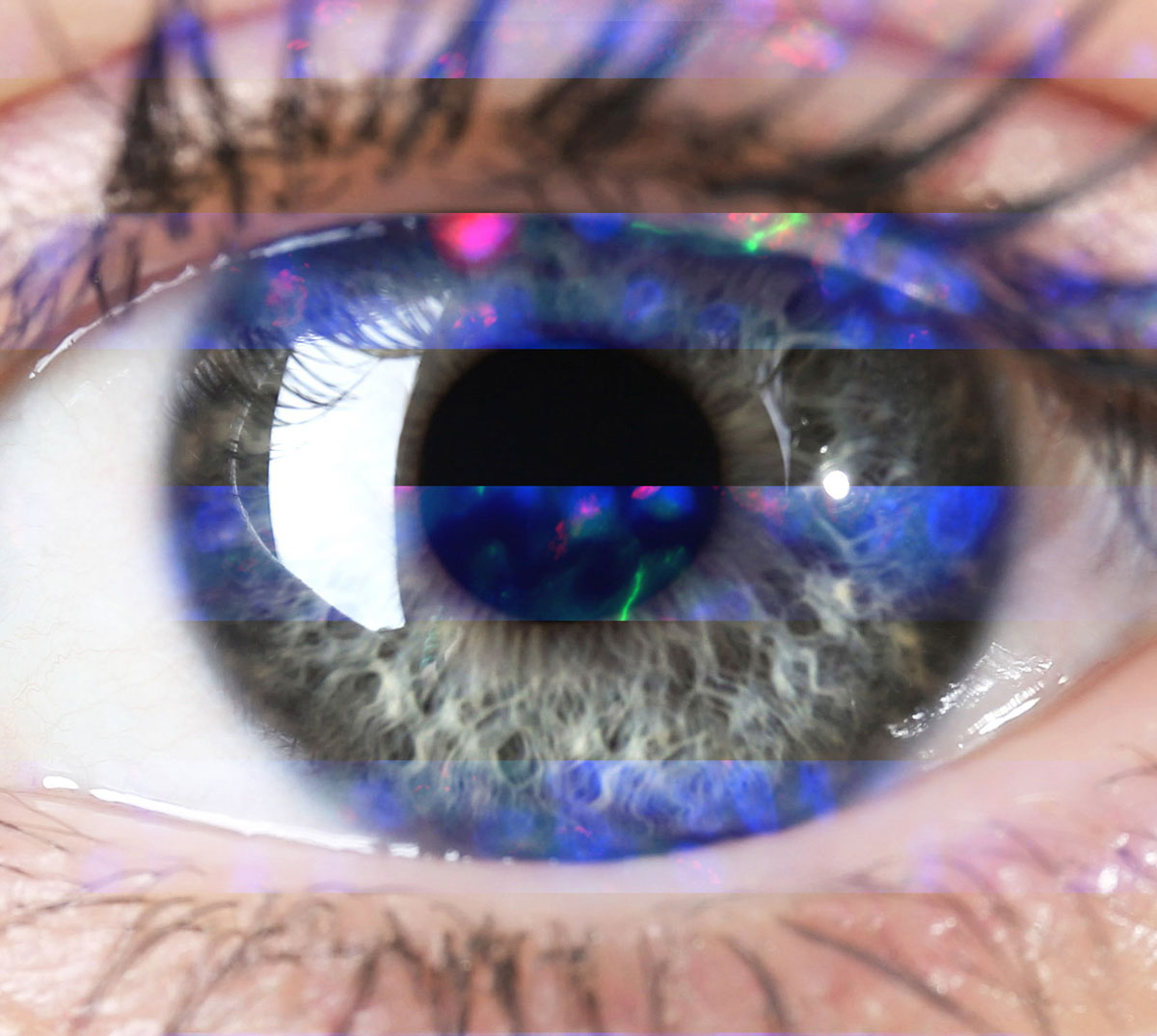

Novel Ways of Looking

February 16, 2017by Jennifer Schaffer Leone

Modernist poet Wallace Stevens’s “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” has been

cited as an exercise in perspectivism. Each of the 13 stanzas expresses an endless

possibility—questions that lead to more questions, thoughts that bleed into new thoughts.

There is a fluidity to his way of looking.

Such an art of observation is often a departure from the field of health care that

necessitates quick differential diagnosis. For seeing—really seeing—isn’t only about

looking outward; it involves looking inward as well.

Such an art of observation is often a departure from the field of health care that

necessitates quick differential diagnosis. For seeing—really seeing—isn’t only about

looking outward; it involves looking inward as well.

This issue of Digest Magazine delves into what it truly means to see—to look in depth, to look beneath the surface

at facets of the body, the mind and the spirit.

For Mindy George-Weinstein, PhD, chief research and science officer, Philadelphia

College of Osteopathic Medicine, and Jacquelyn Gerhart, MS, coordinator, research

support staff and bio-imaging, PCOM, three decades of examination have been spent

in discovery of Myo/Nog cells, which are critical for normal embryonic development.

Their Myo/Nog cells are now the focus of a multi-institutional research consortium that aims to provide a more complete understanding of the impact that the cells have

on tumor growth, wound healing and protecting neurons in diseased retina and brain

tissues.

Bernard F. Master, DO ’66, a successful physician and businessman, has seen and recorded more species—some 7,825—of birds than almost anyone else on

earth. Throughout his medical career, birding provided a respite, a balm and a profound

connection to the natural world that has given him a sense of place like no other.

Jeffrey Gazzara, DO ’16, a neuromusculoskeletal medicine resident at Mercy Health

Muskegon, Michigan, suffers from retinitis pigmentosa. Yet he has adapted to and overcome many of the complexities of practicing with a visual

deficiency through the power of touch and cognition. By interpreting sensory output, he “sees”

health.

Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird

|

I

Among twenty snowy mountains,

The only moving thing

Was the eye of the blackbird.

II

I was of three minds,

Like a tree

In which there are three blackbirds.

III

The blackbird whirled in the autumn winds.

It was a small part of the pantomime.

IV

A man and a woman

Are one.

A man and a woman and a blackbird

Are one.

V

I do not know which to prefer,

The beauty of inflections

Or the beauty of innuendoes,

The blackbird whistling

Or just after.

VI

Icicles filled the long window

With barbaric glass.

The shadow of the blackbird

Crossed it, to and fro.

The mood

Traced in the shadow

An indecipherable cause.

VII

O thin men of Haddam,

Why do you imagine golden birds?

Do you not see how the blackbird

Walks around the feet

Of the women about you?

|

VIII

I know noble accents

And lucid, inescapable rhythms;

But I know, too,

That the blackbird is involved

In what I know.

IX

When the blackbird flew out of sight,

It marked the edge

Of one of many circles.

X

At the sight of blackbirds

Flying in a green light,

Even the bawds of euphony

Would cry out sharply.

XI

He rode over Connecticut

In a glass coach.

Once, a fear pierced him,

In that he mistook

The shadow of his equipage

For blackbirds.

XII

The river is moving.

The blackbird must be flying.

XIII

It was evening all afternoon.

It was snowing

And it was going to snow.

The blackbird sat

In the cedar-limbs.

– Wallace Stevens, 1917

|

Such an art of observation is often a departure from the field of health care that

necessitates quick differential diagnosis. For seeing—really seeing—isn’t only about

looking outward; it involves looking inward as well.

Such an art of observation is often a departure from the field of health care that

necessitates quick differential diagnosis. For seeing—really seeing—isn’t only about

looking outward; it involves looking inward as well.